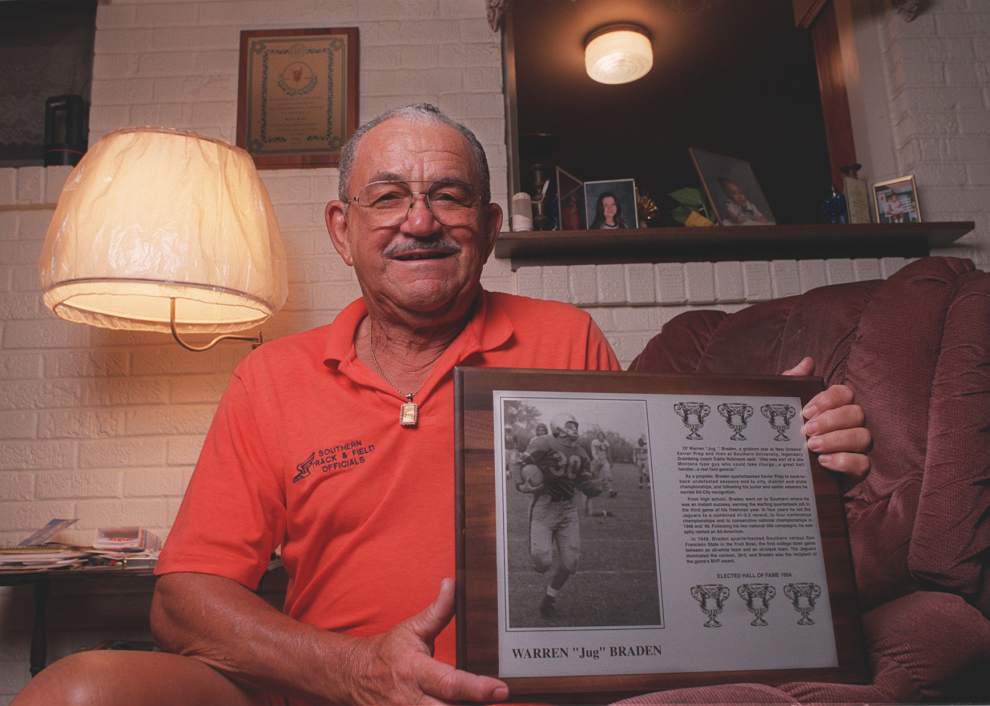

Warren Braden

Sport: Football

Induction Year: 1998

University: Southern

Induction Year: 1998

By Sheldon Mickles

More than a half-century later, Warren Braden still cringes at the thought of making a long walk to the coach’s office at Xavier Prepatory School in New Orleans in the spring of 1944.

Fooling around with a football on the playground one day, Braden accidentally punted the ball into the school’s corridor. A couple of crazy bounces later, it came to rest after crashing into a glass trophy case containing honors won by Xavier’s sports teams.

Upon hearing the commotion, legendary Xavier Prep coach Alfred “Zac” Priestly sprang from his office to confront the perpetrator. But there was no way of knowing it was Braden, a 15-year-old who hadn’t played football in his first two years at the school because he weighed only 140 pounds.

“From where I was standing, no one had ever kicked a football that far,” Braden said. “Coach Priestly came out and wanted to know who kicked the ball and where he was. He said, ‘Bring him to me.’

“I thought I was in big trouble, I just knew I was going to get paddled,” Braden said, his voice turning serious. “I went to his office, and he said he wanted me to try out. He said we might as well put my leg to good use.”

As it turned out, that big boot was the beginning of a remarkable football career for Braden. He helped Xavier win two state titles and then went on to Southern, where, from 1946-49, he was a two-time All-American while playing quarterback and defensive back for A.W. Mumford’s Jaguars.

From a career that started accidentally, Braden’s exploits on the football field have earned him spots in the Southern University Hall of Fame, Nokia Sugar Bowl Hall of Fame and Southwestern Athletic Conference Hall of Fame.

On June 27, Braden will add another honor when he’s inducted into the Louisiana Sports Hall of Fame in Natchitoches, joining Mumford and scores of athletic greats who have left an indelible mark on the state.

“I guess I’ve come full circle,” Braden said.

Even though his career got off to a late start, there was never much doubt Braden would someday play football. Growing up in New Orleans in the 1930s, he learned the game from his two uncles who had earned all-city and all-state recognition two decades earlier.

One of Braden’s uncles, Al Parker, was the player-coach of a semipro team that played every Sunday. Braden, who was raised by his grandmother after his mother died when he was just four months old, said Parker lived nearby and was like a father figure during his formative years.

“Everywhere he went, I was right there with him,” Braden said.

Especially when it came to football. Parker taught his young nephew the game and also gave him punting lessons.

“He was a terrific punter, and people would tell stories about how he’d punt the ball from goal to goal,” Braden said. “I got my punting skills from him.”

It was a good thing, because Braden said he was too little to do anything else when he started high school. At 5-feet-8 and 140 pounds, he concentrated on basketball and track until that day in 1944.

When his time came, he was ready. After making the team as a junior, Braden grew a little and soon became the starting quarterback. With the knowledge he had gained over the years, Braden was a perfect fit to run Priestly’s single-wing offense.

“I always had a good mind for the game because I was around it for as long as I could remember,” Braden explained. “I absorbed everything and I was inquisitive. When I started playing, I knew exactly what to do.”

In addition to playing quarterback, safety and punter, Braden returned kicks on championship teams in 1944 and ’45. Along the way, Priestly hung the nickname “Jughead” (which later was shortened to “Jug”) on his new star.

“I still go by that name,” Braden said with a laugh. “My head was larger than everything else on my body, and they had to get a special helmet for me. I kind of grew into the helmet.”

Accordingly, Braden quickly grew into the game. By the time he graduated and enrolled at Southern, Braden was a polished player who had earned all-city and all-state honors.

Although Southern had run the single-wing in 1945, Braden was in for a surprise when Mumford returned from coaching clinics and put in the T-formation. While some young quarterbacks would have been frightened by a switch to a new offense, Braden was unfazed.

“It was a whole new ballgame, but I took to it like a duck to water,” Braden recalled. “There were so many options and things you could do – you could go in motion, you could split the ends, you could run the wing-T off it.”

Mumford had a quarterback in mind to run his new attack, but Braden took over after the third game and started every game but one by the time his career ended.

In becoming Mumford’s field general, Braden sparked the Jaguars to records of 9-2-1, 10-2, 12-0 and 10-0-1 and black national titles in 1948 and ’49. In his junior and senior seasons, he was selected to the Pittsburgh Courier and Tom Harmon All-America squads.

Official statistics weren’t kept in those days, but former Southern teammate Bill Phillips said Braden racked up incredible numbers.

“Braden was amazing,” said Phillips. “He was a triple threat as a runner, passer and kicker, and he was a good defensive back.

“But he was very clever as a quarterback,” he said. “He was difficult to keep up with, and that was evident by the scores and some of the teams we beat.”

Among those who witnessed the domination by the Braden-led Southern teams was Grambling State coach Eddie Robinson.

“Warren Braden was a sort of Joe Montana type,” Robinson said. “He was a guy who would take charge, and he was a great ball-handler and field general.”

After learning the game from his uncles, Braden honed his skills under Mumford. Becoming so familiar with the Jaguars’ new offense, Braden was more like a coach on the field.

“After practice, I would eat dinner and then walk over to coach Mumford’s house to talk more football,” Braden said. “We would go over all the series until I had it down pat. I really loved the game.”

Once, Mumford was questioned about why he wasn’t sending the plays in to the Jaguars’ offense.

“Coach Mumford said, ‘I’m not worried, Braden’s out there,’ ” Braden remembered. “I called the plays in the huddle and I didn’t take anything from anybody. I chewed guys out for missing assignments because I knew what their assignments were.”

Braden, however, wasn’t always in Mumford’s good graces. When Southern went to Dallas to meet Tuskegee in the Yam Bowl following the 1946 season, Braden was benched.

In the days leading up to the game, the Jaguars were housed at Wiley College in Marshall, Texas. One night, Braden decided to have a little fun and shot some fireworks down a stairwell in the dorm. Unbeknownst to Braden, Mumford was standing at the base of the stairs and almost had his hat knocked off by a wayward missile.

“I ran to my room and waited about 10 minutes and didn’t hear anything,” Braden said. “I went to the door and opened it up and he was standing there. I had a bunch of firecrackers in my hand and he caught me.

“Coach said, ‘Braden, when are you going to grow up?’ ” Braden said. “He said, ‘We’re here to play a football game and you’re shooting firecrackers. You almost blew my damned head off.’ “

When the game came, an embarrassed Braden sat on the bench, his head covered by a raincoat, as Southern struggled to a 14-7 lead at halftime. After conferring with assistant coach Bob Lee, Mumford inserted Braden into the game for the second half. Exploding for 50 points after intermission, the Jaguars rolled to a 64-7 win.

Braden and his teammates helped make history on Dec. 5, 1948, when they played San Francisco State in the first interracial football game.

Dubbed the Fruit Bowl, the game was played in a quagmire in old Kezar Stadium with Southern winning 30-0. Braden was voted the game’s MVP.

“We had a great trip going out there, we all gained 10 or 15 pounds because we had a big dining car all to ourselves on the train,” Braden said. “It was just another ballgame to us, and we were treated fine the whole time. They even had a dance for us after the game.”

Braden, who later had a brief three-week tryout with the Toronto Argonauts of the Canadian Football League, said their coaches never brought up the fact that they were making history.

“Nobody ever played against a white team before, but it was just another game against a well-seasoned team,” he said. “Race never was brought up. We had played the best teams in our league and we were glad to get the competition.”

Likewise, Braden said there was no jealousy about playing across town from LSU, which received most of the media’s attention.

“It was a fact of life,” Braden said without a hint of resentment. “Hell, they went their way and we went ours, and we didn’t think anything of it.”

Later, Braden went his way after being dropped by the Argos.

“I wasn’t disappointed,” he said. “They had a new coach who brought in his own guy. I didn’t get a chance, but I’m not bitter.

“I told some friends that I already had two strikes against me, I was small and I was black,” he said. “You never heard of a black quarterback at that time. I had enough sense to know I wasn’t going to make that team.”

Braden later returned to Southern to earn his degree, and he coached under Mumford after marrying his high school sweetheart, Barbara, who’s been at his side for the last 481/2 years.

Braden spent 34 years as a football and track and field coach – including 26 years at New Orleans’ Carver High – before retiring from the school system.

“The kids of today have so many opportunities, there’s no excuse not to get an education,” he said. “Back then, (blacks) couldn’t even think about getting a scholarship and going to LSU. Now, they have the opportunity.”

And, as Braden proved on that playground some 54 years ago, an opportunity is all you need